25 stories for 25 years. Since 1995, Juxtaposition Arts has provided arts education, employment, and development opportunities for young people in North Minneapolis. In 2020, 25 years since we started our work, we’re sharing 25 stories that help illustrate the impact, growth, and learning opportunities these 25 years have provided. We’re asking some of our alumni, artist collaborators, donors, clients, board and community members, and current program participants to share their stories. Follow along as we share the impact JXTA has had in just a quarter of a century.

For 25 years, Juxtaposition Arts has been a place where youth and artists alike have found resources to better their craft, kinship and constructive critique from fellow creators, opportunities to interrogate and challenge the systems around them, and to reflect on how those systems impacted their own beliefs. JXTA is filled with stories and it exists within a community that often does not have access to its own history. This year, staff and youth apprentices at Juxtaposition Arts have begun building a cultural archive to be housed within the organization. This archive will document the history of the organization and its neighborhood, creating an accessible space for Northside stories to be held within the geography and culture that created them. JXTA Co-Founder and Chief Cultural Producer, Roger Cummings, and Project Coordinator, Dr. Tia-Simone Gardner, were interviewed by JXTA youth apprentices Cecilia Andrade-Vital and Laurel Prenzlow about this project.

Where did the idea for the Archive come from?

Roger: The idea was informed by a few things. I collect a lot of ephemera items – all of my sketchbooks from 14 years old all the way up to all my love letters, letters from friends who went to jail, cassette tapes, old recorded TV episodes. I believe there should be places in communities of color where people feel comfortable contributing their stories, objects, and artifacts. A place that can be seen for generations in the context of our culture.

People outside of your culture shouldn’t be holding your history. In the Minnesota History Center, there are pictures of a photographer Charles Chamblis. In the 1980s, he would go to nightclubs Downtown and parties in North Minneapolis to take pictures of people. All those pictures are now in the History Center. A book was published about that work, but it doesn’t consider the work’s context and doesn’t tell the work’s full story. It’s important for us to be able to have control of our narratives, our histories, and our objects, rather than having to leave my community and go over to the History Center to learn about myself and my culture. Even as a young person going to the Bell Museum, it would strike me as bizarre when I would see everybody’s different cultural garments on display. Context is key. If things are out of context, it distorts narrative and perception. I thought it would be better for Northside cultural objects to live near the people and culture from which they originated.

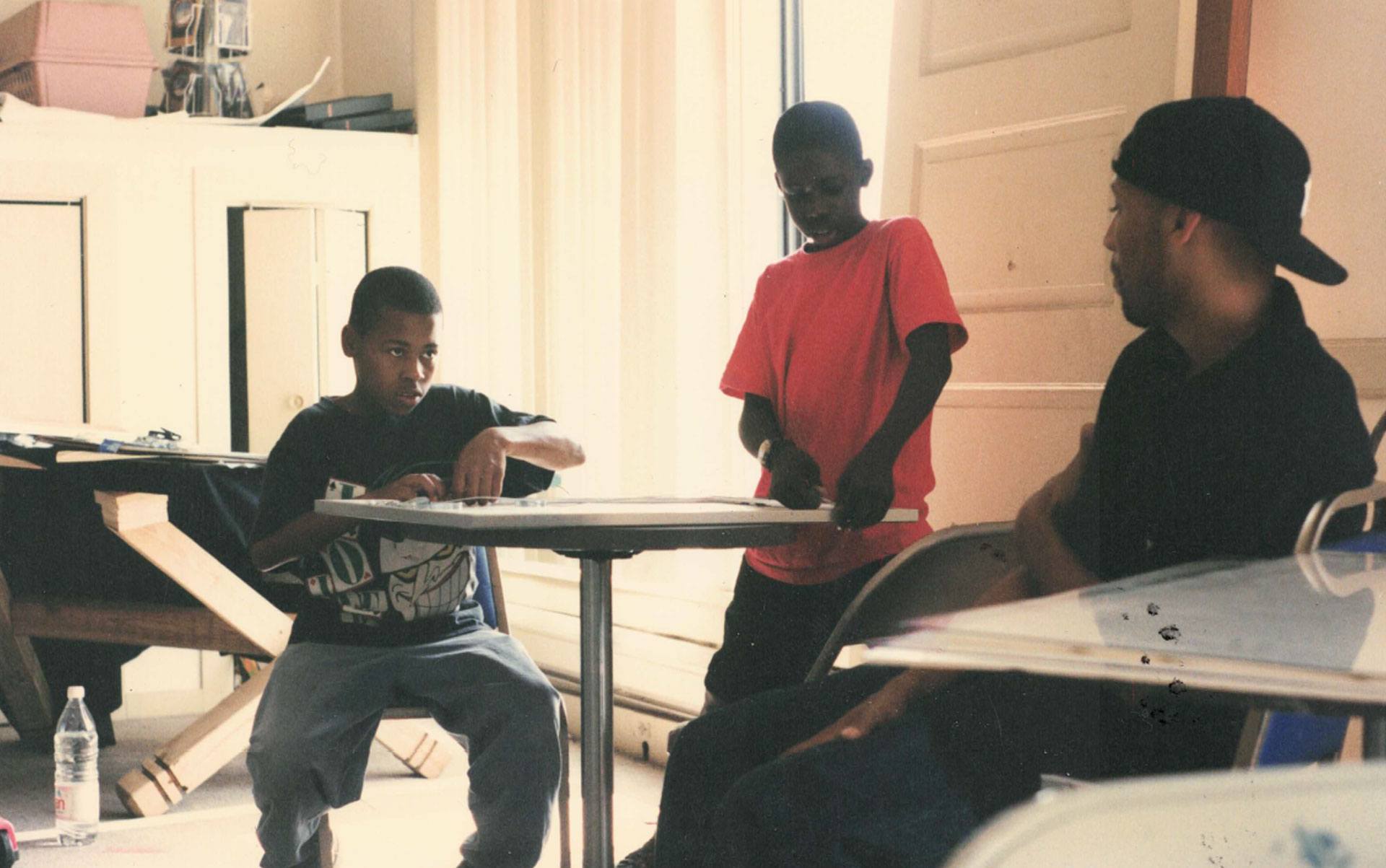

The first VALT sessions in 1995 took place in Sumner Olson public housing.

How is JXTA going about creating the Archive? What is being included in it?

Tia: First we are taking inventory of everything on the JXTA campus that should go in the archive – documents, event fliers, artwork from past students and teaching artists, old photos and video, youth-designed t-shirts, and more. We’re digitizing that material by scanning or photographing it and storing it in our data system. We’ll then take that inventory list and turn it into a finding aid, which is a kind of guide that shows information about what is in the archive. Once we get a handle on our own materials, we will begin inviting our Northside neighbors to contribute materials they would like to enter into the archive. In the future, these digital files will be made available via a searchable web-based database that people can visit and see the archive. The actual objects will be stored in our new campus and accessible to Northsiders and other visitors. We’ve also begun collecting oral history interviews from present and former staff at JXTA. Along with being an opportunity to learn from the growth of JXTA in the last 25 years, this project is also a way to find folks who are no longer at JXTA, but have memories and information and can contribute to the history of the organization.

A mural project in 1998.

The vision for this archive includes stewardship by JXTA youth apprentices. Once the archive is complete, caring for it will become part of the training that apprentices receive as artists and researchers. To this end, apprentices have been a part of collecting oral history interviews with current and former apprentices, which will become part of the archive.

We were provided some support for this step from the Center of Urban and Regional Affairs in the form of graduate student Prabana Mendis, who is working on the project with us. Northsider Yonci Jameson has also contributed to the inventory and digitizing effort as well.

Will people beyond JXTA be able to contribute to it and see what’s included in it?

Tia: Yes. The Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture hosts History Days where they assist people in photographing keepsakes and family photos that can be added to the institution’s archive. This way, the owner gets to keep their artifacts and their stories are simultaneously documented by the Smithsonian. That’s what we hope to do, but in a hyper-local sense. We want our neighbors’ stories to stay in our community. Before this happens, though, we’d like to set up a system that can make it easy for individuals to add to the archive in this way. This is why we’re starting by creating an inventory of what JXTA already has.

The first VALT sessions in 1995 took place in Sumner Olson public housing.

In addition to the archive being in North Minneapolis, the digital aspect of the archive will make it accessible to anyone with an internet connection. We want it to be easy for people to see and understand what is in the archive regardless of how they’re able to access it. We also want to be adaptable, given that the nature of youth and culture are iterative – both change over time.

Aside from its historical importance and relevance to Northsiders, we anticipate that many artists, researchers, curators, and activists will be interested in this archive. We hope to create a cultural asset that is owned by the Northside.

Why is an archive important for JXTA and for the Northside?

Roger: Young people are often underestimated and their ability to innovate is misunderstood. There is no successful social or cultural movement in history that did not require the buy-in and energy of young people. We want to create this archive to honor that fierceness and that flavor so that our community doesn’t forget that. It’s part of our history as an organization – JXTA was founded by Black people who were in their twenties. Historical and cultural context is important to any narrative. The documents and cultural artifacts that make up this archive, and the narratives within them, will give historical context to what is happening today.

The truth about young peoples’ and Black peoples’ ability to innovate is not a unique characteristic to the Northside, either. We want to be able to take this archive to different historically Black neighborhoods with similar histories of marginalization, such as Gary, Indiana and the Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles, and build relationships there in an effort to change that narrative of our neighborhoods to something more realistic and representative. We have a lot to contribute, just like everybody else. North Minneapolis is not any more dangerous than any other place. I think that’s why it’s important to have a cultural archive in North Minneapolis, similar to why the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is important to have in Harlem.

The first VALT sessions in 1995 took place in Sumner Olson public housing.

Are there any ways that people can support the Archive project?

Tia: If you have resources, expertise, or time to contribute, we’d love to find ways to be able to collaborate in creating infrastructure for the archives. Otherwise, people can support this project by supporting JXTA’s Capital and Legacy Campaign. As the only Black-led art and design organization in North Minneapolis, this campaign is an investment in our facilities, our programming, and the creative futures of our young people. The archives will be located within the new facility that the Capital Campaign will fund.

Additionally, we anticipate that Northsiders will be able to contribute stories and objects. We will share more information on how to participate in the coming months.

Roger: Yes, support the Capital Campaign. Representation is so important, and as a Black-led organization, it is one of our goals to provide that for our young people. They need to see people who look like them building buildings, creating institutions, and crafting legacy. I think that’s super important for every culture. You never know how important your support, assistance, and research is.